ALL THE WINE

Two Saturdays ago I woke up in Ann Arbor on an inflatable mattress on the floor of a friend’s apartment. You know how the rest goes.

If you type in Denard Robinson on Google the first suggestion is "Denard Robinson Heisman." He doesn't know what they say about him on television because he doesn’t have cable. Notre Dame let him in the interview room and it was the first time an opposing player has been allowed in there since 1997. Dick Vitale spent Saturday afternoon telling Jalen Rose over Twitter that Denard Robinson was awesome, baby. Lebron James said he was “a monster out there right now.” Denard Robinson is from a different dimension. We can only swarm to the crater where he crash landed and pick through the debris for souvenirs.

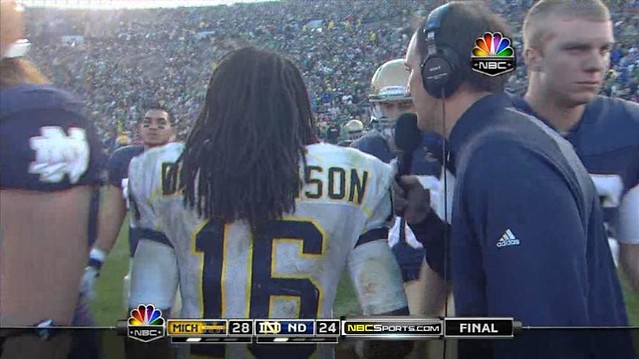

Spectators have an immediate need to formulate a narrative. But Denard has undergone no distillation. He is raw, unconscious, disappearing over the horizon with his arm dangling out the window. There is no calculation; no bravura nor is there gruff introversion. He is just alone in the middle of thousands of people who scream his name while he tries to get the hell out of there. The game ends and there are 25 people with wires dragging behind them who converge to ask him why and how and when he knew and really to just stand and stare and wait for him to say something profound. But he keeps walking. He says nothing and then runs off to follow someone who he recognizes into the tunnel.

Only once on Saturday did Denard look uncomfortable: when it was over, as he wandered around looking for Nate Montana, and Doug Karsch kept putting a microphone in front of his face.

He has done nothing personally to embellish the mythology. Tate didn’t remember his name on Signing Day. Recruiting sites thought he’d only make it as a corner back. The hair that hangs down his back, the teeth that glow like some kind of nuclear ooze seeping from a bio-hazard drum. It is just there. He doesn’t embrace it and he isn’t even ambivalent about it. “Who are you?” they seem to ask. He laughs and stares at the ground. “Do I have to keep talking?” He crosses the goal line and immediately falls to one knee, as if God was up there tapping on his watch and Denard had to apologize for taking so long. He is as discreet as someone who has amassed eight-hundred-and-eighty-five yards in two games is capable of being. Which is to say he’s about as discreet as someone who walks into an orphanage with a keg of moonshine on his shoulder and a cigar in his mouth and tosses $26 worth of firecrackers into a toilet bowl.

Every sentence begins with an impulse, a spasm, and then they end with him smiling and looking somewhere else, trying to give you a phrase he’s heard before. He nearly said, “I played good” but corrected himself and proudly said, “I played well.”

In an interview after the UConn game, an old man asked Denard about his touchdown. And Denard said, “Oh man … I was just ready, I was just ready to run and ready to go. I knew I was gonna break one, at least. I had ran … I ran it, uh, I think I had ran it three times, and it was just like, ‘Alright, time to get it in the endzone.’”

The game amuses him. Football is a Herculean beast that crushes players in its fists into a bloody paste. There are fleeting moments of bliss but ultimately it will ruin you. To Denard it will not. It is something to be conquered, an equation written on a chalkboard. And he solves it by kicking a hole through the window and setting the entire school on fire. He defies even the most grandiose hyperbole. So we will say this: Denard Robinson has more rushing yards than any other person in the country. He has 41 more yards than the next guy. And that guy did it against Washington State and Troy.

Describing his speed is like explaining to a blind person what colors look like or how big a mountain is. Hold this rock in your hand, only imagine a rock that your hand or a bigger hand or a million bigger hands could not close around. That’s a mountain. Something like that. His first 10 runs against Notre Dame went: 4, 2, 3, 9, 36, 6, 14, 2, 7, 87. Eventually, you just lose. You are working against one of the principle dynamics of the universe: Denard Robinson is fast. If you’re behind him it won’t end well.

This is not Mike Hart frantically looking over each shoulder like he was being chased by a dinosaur holding the top seven stories of a building in its mouth. Denard’s runs are moments of extreme calm. A decision, a pivot, a man running in a straight line. He is a trail of gasoline swallowing a lit cigarette. My memories are not of a few uninterrupted seconds of him running but of static images. He is here and then he is there and in between is a narcotic haze. We are entranced. There were people jumping in front of me and behind me and, at some point, I was knocked between the rows by someone who had forgotten where he was and impulsively grabbed my shoulders to steady himself while he watched Denard disappear.

"I don't think he'll be taken by the storm," said Dave Molk.

There is no vanity, no self-preservation. He never slides or veers out of bounds. He is oblivious to the idea of something existing beyond this moment. Quarterbacks avoid contact as if it were a biological imperative and yet Denard leaps and is suspended almost perfectly horizontal while limbs covered in thin fabric are pulverized from all angles. He does it not for the distance itself but for an idea: to relinquish anything is a tragedy. The first down is right there, I can see it in front of my face. The future is an abstract concept that does not scare me. I am just here and I am lying in the grass telling you that I don’t tie my shoes because I never have, and when it’s time, I am running until I have to squint to see straight while they give me the play from the sideline. But then I am running again; I am running and they still can’t catch me. Sometimes he looks like he just ran headfirst into the Atlantic and kept running until he reversed the tides. And then he leans over to keep from falling down. “I don’t like being caught from behind,” he says. He’s not being coy. He’d just prefer that it doesn’t happen.

He says this: “I mean, uh, when they call my number, and the offensive line is blocking like that, and it’s God willing, and God engineering, I mean, I can do whatever.” You can thank God for the cab fare, I guess. You’ve been doing just fine on your own since you got here.

He is not tired. He is not hurt. He does not know what storm you’re talking about.