When you hear a familiar voice in the middle of nowhere, it takes you by surprise before it puts your heart at ease. It was dark and there were only stop lights and high beams, and Lloyd Carr was calling to apologize for taking so long to call me back. I’d like to tell you that this was a fairly insignificant moment in my life, that I’m a journalist and objective and immune to brazen sentimentality. But that wouldn’t be right. That would be a lie. Last night I rented My Best Friend’s Wedding and ate reheated empanadas and cherry Sprite, and fell asleep on the couch listening to Curtis Mayfield. This was a very significant moment in my life.

I think about it while I’m covering a high school baseball game in some Connecticut suburb carved out of grass and hills and astonishing blandness. I think about it when it's windy and it’s cold even in the sunlight, and the five dimes in my car’s ash tray stuck to cough drops and dried up Dr. Pepper gets me a bag of Fritos between innings.

I think about it when Rich Rodriguez is forthcoming and speaking loudly and I remember how Lloyd’s sentences wandered in three different directions and sometimes in no place at all. His voice sounds like a man’s conscience, in both tone and content, and in private, away from the podium, he sounded as defiant as ever, if a little more comfortable being philosophical.

I wrote a profile on Lloyd for this year’s edition of Hail to the Victors, and by the grace of God and the help a certain beat writer I was able to interview him over the phone. Of course, these instances are inherently dangerous: If Lloyd turned out to be a bad or even mediocre person, the last 13 years of my life would mostly be a lie. But none of that came even remotely close to happening.

On a Sunday night two months ago, he called me and he said the next Wednesday at 7:30 would work for an interview. I called him then and there was no answer, and at 9:30 I still hadn’t heard from him. Then the phone rings; it’s him. “So John, I’m watching this debate…Clinton and Obama.” Those were the first words out of his mouth; he sounded pensive and was entirely serious. I hesitated, and before I could respond he said, “You mean you’re not watching it?!” I told him I’d been sitting around for two hours waiting for our interview. I tried to sound sarcastic and jokingly make him feel irresponsible, but in the end I think I just came across as needy and politically uninformed. He chuckled and told me to call him back when it was over.

When we spoke again, I asked him what he thought of the debate. “I thought it was the best of the debates that I’ve watched,” he said. “I haven’t watched them all but I’ve watched a lot of them. I thought Hillary put Obama on the defensive. But I thought he handled himself well. But I thought she, you know, she was aggressive. You know I think they’ve both improved dramatically over the course of this campaign. And it’s been, ha, as tough a campaign as I remember.”

This all sounded so familiar. The players were different, but this was very much still a coach doing what he did best. Lloyd didn’t comment on how each of the two candidates vowed to handle threat of a recession, oil prices, or Iraq. He talked about their tactics, their progression, how they responded to adversity, and where this small debate stood in the vast overall narrative of the season. Sorry, make that “campaign”. He asked me if I liked politics, and I told him that I admired Obama’s skills as an orator and thought that a man who could quote Kipling off the top of his head might have felt the same way.

“Well I think he’s a great story in terms of his birth and his adolescence and where he’s come from,” he said. “And he is…he has an ability I think to inspire people. And you know, I don’t think there’s been an American politician since JFK where young people have really been this big part of the campaign. All over the country there’s more interest by the young people, and percentage wise a great majority of them are for Obama. And I think that speaks to his ability to inspire. And the question will be, what kind of leader he is, and how tough he is. I think those are the questions that he’s going to have to deal with in this campaign if he gets nominated.”

Here are the parts of our interview which weren’t published in the Hail to the Victors piece:

On how closely he has been following the progress of the team:

LC: I been busy, I spent a lot of my time with my staff, I’m really delighted with the jobs that they’ve come up with. That took a while, and then primarily I’ve been trying to get organized…I’ve given a few speeches, had some discussions about teaching a class next year. And I’m going to go to China here at the end of may with a group that president Clinton has put together. We’re going to go visit Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, and I think that’s going be a very exciting trip because of the Olympics and all the issues…with the global economy and the role that China has played in it.

On developing the kids as players vs. developing them as human beings:

LC: Well john this is my concept of our job: as the head coach at Michigan- number one we're going to have a team that consistently plays championship football. Secondly a program that was run with absolute integrity. Third to have a program that at the end of the day the players when they left and when they were done felt like they had an experience that would be beneficial to them after they had finished their careers. And experiences that were worthwhile as far as some of the values that they developed because of the competition they had while they performed here.. and last to have a program that people who loved this university could be proud of. Those are the guide marks, the guide posts that I always kept in mind as I tried to do things in terms of building this program. So I think the answer to your specific question- you have to win as a coach, because if you want to stay you got to win. If you don’t win you’re not going to get to stay, and we all know that as coaches. And that’s fair. But I think along with that, I just always believed that there were a lot of things that you could learn in sport and athletics that you could learn in very few other things. And I think those things are important. So that’s what I tried to do.

On his players’ availability to the media, and how some critics felt they weren’t available enough:

LC: Yeah I didn’t care about that. There’s no body that got more exposure than Michigan football players. I think what I always tried to keep in mind was that our players, first and foremost, were trying to get a college education. And one of my jobs was to make sure that they had every single minute that we could get them outside of practice, that we didn’t waste their time, and we didn’t put demands on them like those that are put on professional athletes. And that’s the thing that a lot of writers didn’t understand. They don’t differentiate between college and professional athletes. I never listened to it, because I knew what I wanted to do, and I knew what my job was, so that never impacted me.

Why he didn’t campaign for the title game in ‘06 after the loss to Ohio State:

LC: Well, because I don’t think that what’s the system is supposed to be. It’s what you did on the field. And I just felt that was something that a Michigan coach shouldn’t do, and I wasn’t willing to do it, and I’m glad I didn’t do it.

Another part of the interview, which was absolutely vintage Carr: I asked him about this comment that he made during his retirement press conference: “What it takes is an all-consuming enthusiasm, energy and passion. I had all those things, but, by the same token, I knew there were things I didn't want to do anymore.” Specifically, I asked him if he had gradually lost that enthusiasm, or if the ’07 season did most of the damage. He said, and did not elaborate, “I think it’s exactly what I said that day, John.”

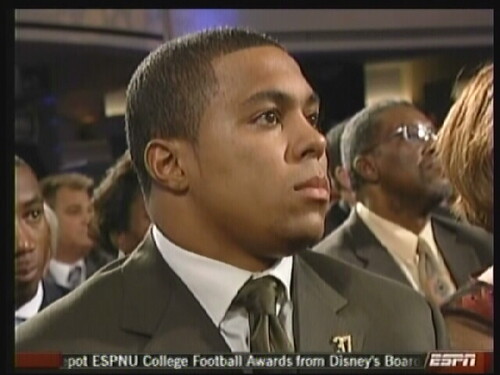

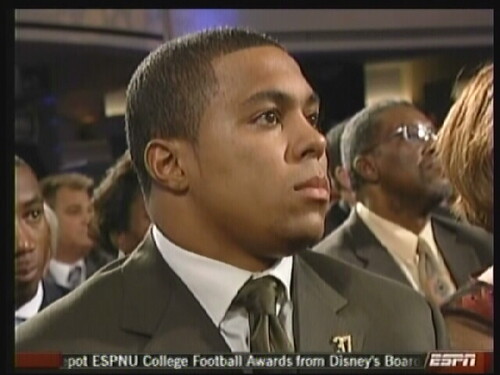

When it was over, when Michigan beat Florida, the tone wasn't maudlin or even nostalgic. It was really just one sigh of relief. Yes, as far as farewells go, a win in the Citrus Bowl is the equivalent of an elevator music rendition of a love ballad, but it was all I needed to survive. Lloyd won the last game he will ever coach, and then he left; there was no more. That liberated, maniacal offense wasn’t the way we knew Michigan, and it wasn’t the way we will remember them.

But on dark nights, when you’re in the middle of nowhere and the only familiar voice is the one in your head, you’ll tell yourself that those moments are all you need. You’ll tell yourself that you met a few good men and loved them enough to cry when you had to see them go. And maybe the voice will sound a little bit like Lloyd’s.